Aluminium is Precious - The Untold Story of BMX Innovators KHE Bikes, Part 1

"Some started bike companies to save their lives, others just wanted to solve the simple problems they were facing everyday"

Words by Thomas Fritscher | Images courtesy of KHE Bikes & Kay Clauberg

Whilst nowadays people might start a bike company to promote a certain image or to ‘hook people up', the idea was a completely different one 35 years ago. At the time BMX bikes were flimsy, fragile and product innovation was stagnating. Large companies turned their backs on BMX, looking for money somewhere else (cough, cough… MTB). But BMX was moving fast - people rode like they meant it and it would be fair to say that the face of the ‘sport’ we know was shaped in those years of non-existent public interest.

The bikes of the time were mostly still shit though, so riders started looking for solutions. Some started a bike company to save their lives, others just wanted to solve the simple problems they were facing every day such as bent axles, folding dropouts, and breaking parts. Across the world product selection was a joke too; a wide range of about four different frames, two sets of handlebars and three kinds of tires were all that was readily available… and that was if you were lucky enough to have a bike shop around.

How it all started. Thomas Göring at the local BMX track Rheinstrandsiedlung in Karlsruhe circa 1984.

KHE's first logo. Proudly hand drawn by Thomas on the glass table in his apartment.

But BMX didn’t stop. The bolt-on gadgets that looked cool in neon adverts were replaced by axle pegs which fuelled progression towards more difficult/less flashy rolling tricks. Picking the right pegs was a tough task though. You had Skyway ‘Axle Extenders’, made out of soft aluminium, basically a long-ish 10mm axle nut. They were ridiculously slim by today’s standard and about two inches long. The second choice was arguably the best: chromoly GT ‘Tube Rides’. These were obscenely heavy, significantly shorter than the Skyway pegs and featuring a sharp, open end tube, which earned them the honourable nickname “cookie cutters”.

17 year old Thomas Göring was part of a tight group of flatlanders from Karlsruhe, Germany back then. A proper old school dude, with deep roots in the young sport, riding every day and facing all of these issues and more. But he was also in training to become a precision engineer. Some of this stuff seemed ridiculous to him. He was machining quality aluminium alloy by day while stripping the threads out of butter soft bike parts or breaking injection moulded crap after work. This could not stand. His brother had just received the first loan from his job at the German Postal Service and together they did what every self respecting freestyler and their brother would do in this situation; they bought a pocket size lathe and some leftover pieces of quality aluminium to create what would become the first KHE product, the Do-Peg. These were relatively large pegs with a comfortable concave design at a fraction of the weight of the dreaded GT die-cutters. Like all pegs back then, these replaced the axle nuts, so the aluminium quality was crucial. KHE’s peg was a big step up from everything available back then - not least because of the fact that you couldn’t strip the thread with your bare hands. So it didn’t come as a surprise that people who saw these pegs on Thomas’ bike wanted some for themselves.

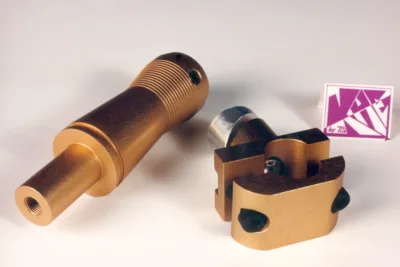

Thomas's first ever peg. Handmade under the strict supervision of Arnold "Pumping Iron" Schwarzenegger, whose poster graced the wall of Thomas's cellar apartment

The second version of the Do peg was a proper product. Mass manufactured (well, more than 10) to exact specification and featuring the two different threads on either side. One for caoster- and the other one for freewheel/front hubs. Why this difference was made remains a secret but at least now you wouldn't have to worry about it anymore.

"His brother had just received the first loan from his job at the German Postal Service and together they did what every self respecting freestyler and their brother would do in this situation; they bought a pocket size lathe and some leftover pieces of quality aluminium to create what would become the first KHE product, the Do-Peg."

Soon the friends were equipped with the new product and stuff needed to move into a more official, orderly fashion. This is Germany after all. Thomas and his elder Brother Wolfgang founded KHE Bikes in 1988 and what started as a simple idea to make life a little better was now officially a company. Over nights and nights of tedious work, Thomas managed to fill a cigar box with pegs which he brought to the contest. And the response was instantly overwhelming. He then began selling his pegs through German bike shops, designed a logo and created the first print adverts, all from his basement apartment in Karlsruhe.

While the original Do-Peg still had a 'homemade' feel to it, with lengths varying according to the pieces of aluminum Thomas found, the Do Peg V2 from 1989 was a real proper product. With an improved shape and featuring two threads, the “regular” 26TPI on one side and 24TPI, (which was used on coaster brake hubs) on the other, it quickly became a scene favorite. Fueled by its success, Thomas started experimenting. Still riding every day with some of the best flatlanders in Europe there was never any shortage of inspiration or ideas. Local legends Albert Retey and Christian Wendland helped Thomas come up with new ideas in exchange for decent parts that wouldn’t break every other day. They would become KHE’s first team riders, with Albert being the obvious flagship rider. He was an immensely talented rider who ironically had a reputation for riding ‘pile-of-crap’ bikes and not really caring about which parts he was using. He became the showcase for KHE’s ideas as he rose to the status of one of Europe’s, and then the World’s, best flatlanders.

KHE's first 'office' was a spare room in Wolfgang's apartment.

Thomas Göring on an SE Quadangle around 1988. You might be able to spot some really interesting parts in this photo

Albert Retey on what he would call 'a perfectly suitable bike'. This is from around the time in 1988 when he first started to go to contests.

Some of these ideas were as easy and effective as giant aluminium washers to support the flimsy dropouts of the past or as niche as little rings to go between grip and bar-end to save the bar from the torment of endless hitchhiker practice. Thomas designed and produced a double decker seat post clamp to stop frames from cracking in that area - an idea that caught on and was soon produced by all the major players in that market (all three of them). He also worked on stems to replace the very popular ACS 45 and 55 stems which while being aesthetically quite pleasing had the tendency to not really last any longer than a few weeks. KHE also ventured into the soft goods market with Christian Wendland sewing neoprene shin pads and gyro pads (remember those?) on his Mom's sewing machine.

One of the more complicated ideas came due to the fact that forks were constantly breaking. The problem Thomas and the flatland community was facing was different than the ones ramp riders had and fortunately not as life threatening but when a dropout of a two week old fork simply falls off because the axle broke it does get somewhat frustrating. Thomas didn’t have access to any bending or welding machinery (yet) but what he did have was the ability to machine complex stuff out of aluminium. The result was a fork made out of three straight chromoly tubes and three machined blocks of aluminium keeping it all together. It’s somewhat unusual, and clunky look earned it the name “Schlachtschiff” (Battleship) but especially because of the lower parts replacing the flimsy dropouts, it proved to be a good idea which saved a few axles on the way to eventually being replaced by more sturdy dropouts and axles.

The bottom part of the Schlachtschiff fork featured these unique 'stems' that clamped the pegs into place a offer more stability than the tin foil dropouts of the late 80s. People would sometime hacksaw the dropouts of their regular forks of and used these as a replacement.

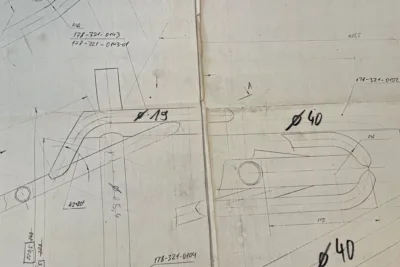

The bottom part of the 'Schlachtschiff' fork in a technical drawing.

The man himself. Thomas Göring with a backward rubber rider around 1988 at the roller rink in Kenn, where the Worlds were hosted in 1989. Note the first Do Pegs on his bike.

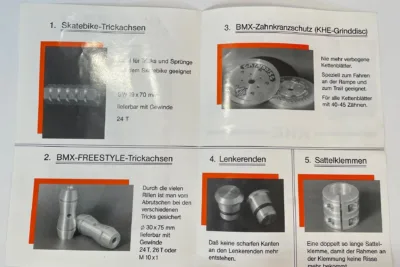

The cover of the first KHE catalogue printed in 1989.

Inside the first catalogue. Thomas rode at shows for a 'skate bike' company back then and used this opportunity to sell pegs to them.

By now people wanted bigger pegs. Street riding had caught on and riders managed to strip the thread of even the best available aluminium pegs. The socket type peg we use today was nowhere to be seen yet (even though Uni introduced their socket style ‘Tail Pipes’ in 1984 but they were of such strange proportions that they went mostly unnoticed). In 1989 Thomas came up with the somewhat over-engineered idea of using a steel adapter nut with a big thread, where a bigger peg was attached. This second generation KHE peg - aptly labelled ‘Fuß’ - sported an almost modern size with the patented KHE concave design and pattern. These pegs were a huge step forward in terms of comfort and durability and caught on like wildfire. He extended the range even further with the ‘Tonnen’, which sported a knurled surface and no concave. When the socket style pegs were finally made popular from the likes of Burp, Pulse and later Standard, KHE added those to their growing peg-folio as well. And thanks to the over engineering of the Fuß-Peg, everyone was now in possession of two sets of ultra strong axle nuts to replace the ever-stripping nuts on the old 10mm hubs.

KHE's second Peg 'Fuß' (Fuss) featured a tough axle net that would act as an adapter to take stress of the aluminium threads.

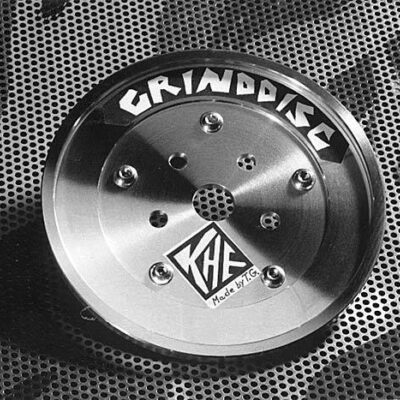

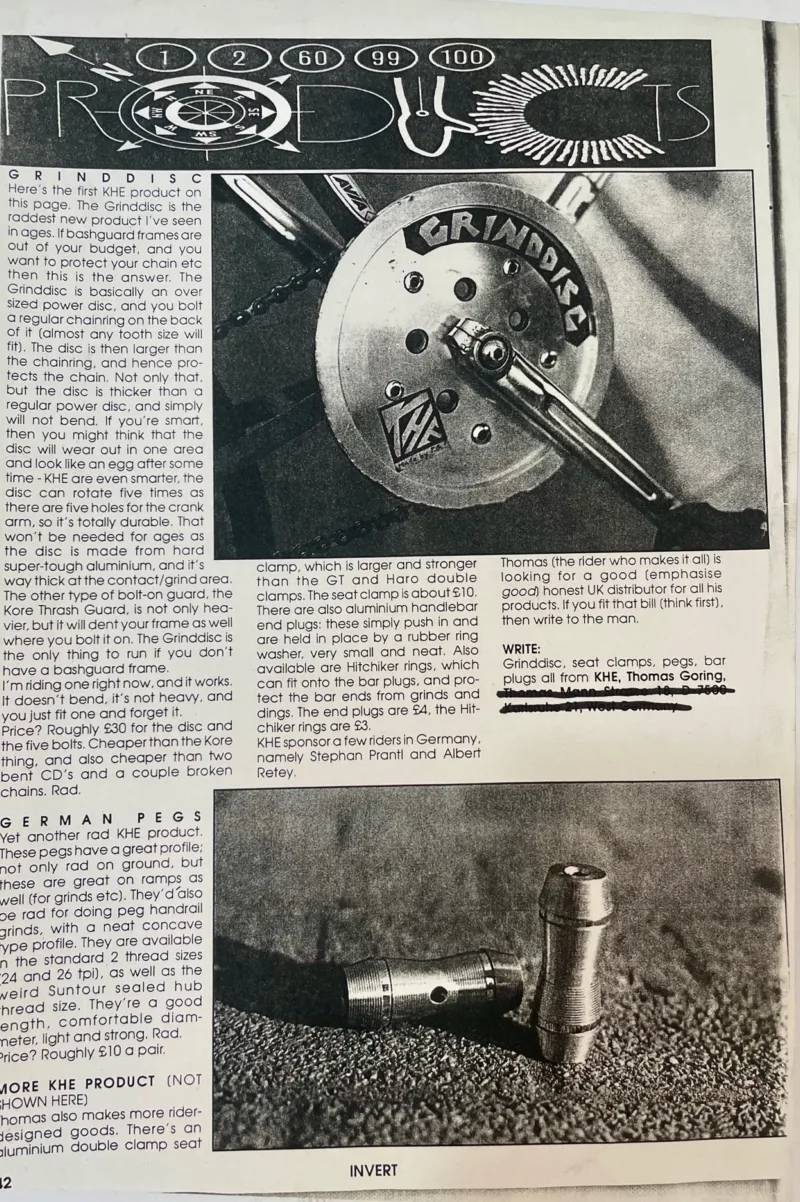

The OG Grind Disc was massive and sported 5 big screws to attach a chainring.

But there was one product that really helped get KHE noticed outside of the flatland bubble, and outside of Germany for that matter - The Grind Disc. Designed by Albert Retey, it came out around the same time as the Havoc Sprocket Pocket but was machined out of solid aluminium. Since this wasn’t on everybody's Insta-story back then it’s hard to tell which came out first and I guess it doesn’t really matter. Grind Disc was an impressive pie plate of a “spider” replacement, made to take a 44 something Sugino chainring and protect it and the chrome plated Shimano chain from impact. If you can’t figure out what this actually means, think ‘Guard Sprocket’, but about twice the size. It made the somewhat obscene idea of bashguard frames obsolete and came at a time when a rather destructive type of street riding was all the rage. Stephan Prantl took a few with him on a plane to the US where they ended up on the bikes of Jay Miron, Pete Augustin and Mat Hoffman. Grind Disc put KHE on the map and into the international press. Their stuff ended up in the legendary Go! Magazine and was regularly praised by UK magazines too.

Invert magazine, and later Ride UK, always loved KHE products and along with the English team riders helped KHE establish the brand in the UK and beyond.

With this gained momentum Thomas managed to recruit some of the guys that made up KHE’s first international team. Albert and Christian were already team riders from the start and considered part of the company. They were joined very early by Marc Matter, one of the early pioneers of street and dirt riding and long time friend Armin Batoumeni from France. Mike Canning and Phil Dolan joined the team in late 1991 and KHE even co-sponsored the enigmatic Chase Gouin in 1992.

The first product range with the Schlachtschiff fork, Hitchhiker Rings, Fuß- and Do Pegs, Grind Disc and the double decker seatpost clamp.

Marc Matter is an old school flatlander and 'Zine maker who was one of the first german riders to ditch the platforms and turn to street and dirt. His aggressive and innovative antics left quite a mark on the scene back then.

KHE's first 'official' Team photo shot at the King Of Concrete in Southsea skatepark 1992. Top: Chase Gouin, Armin Batoumeni Bottom: Marc Matter, Phil Dolan, Mike Canning, Thomas Göring and Albert Retey.

It was quite early on that Thomas zoomed in on what could be called the ultimate challenge in BMX technology; The freecoaster hub. Every (free)-coaster hub back then was based on the basic Suntour coaster brake design. It was the best rendition of the basic coaster brake found in beach cruisers and cheap kids bikes. Riders collected spare parts, hoarded axles and knew the internals of the hub by heart. You removed the actual brake pads, maybe threw in some washers to reduce the slack (later cleverly marketed as “un-brake” by Standard Bykes), filled the whole thing up with grease and fine tuned the cone nuts for a smooth rolling experience until the axle bent, which could very well have been the same afternoon. Stronger axles mitigated some of these problems but it was clear that the design wasn’t perfect for the use case. Suntour coasters were designed to be used as a brake, which meant they sported a heavy duty steel housing made to withstand crazy skids and, later, Bob Haro performing drop-in variations. This of course made the whole thing unreasonably heavy and the loose ball bearings would often leave their marks and destroy the increasingly rare hub shells.

KHE's "Rollvergnügen" Freecoaster hub featured a radical redesign from the traditional coaster brake.

"The freecoaster remains a project close to heart for Thomas and is an important factor in KHE’s status in the flatland scene."

Thomas took on the challenge and in 1991 engineered “Rollvergnügen”, KHE’s first entry to the coaster market, featuring a radical new design with sealed bearings and a lightweight shell. It incorporated a spring that would automatically disengage the hub when you took your feet off the pedals and even though it wasn’t perfect it was a milestone and it would take years until other companies stopped marketing rebranded Suntours and tried their hands on self-engineered coaster hubs. The concept itself turned out to be too complicated (and error prone) for mass production - since it requires it’s parts to be manufactured with very little tolerances in order to work properly - so they later refined the freecoaster hubs and included a patented system to adjust the slack from the outside. The freecoaster remains a project close to heart for Thomas and is an important factor in KHE’s status in the flatland scene.

By now the business had grown to be way too big for the tiny lathe in Thomas` two bedroom apartment so they began outsourcing. First to a local machine shop that could make larger quantities of pegs and anything made out of aluminium along with simple steel works, but the time was right to venture into the 4130 chromoly market and the business of bending and welding tubes. At the Eurobike trade show Thomas approached a company showcasing rather cheap bikes about stocking their fleet with KHE pegs. It turned out this company from Minsk, Russia was an actual manufacturer and had everything that was necessary to build and produce bike parts. What they were lacking was the proper materials and knowledge. So Thomas not only walked away with a deal to get larger numbers of pegs produced at a better price but also the prospect of getting more complex chromoly products made for his company.

The original drawing of the KHE Catweazle frame. Sent of to Russia (with love).

As it turned out however finding the ‘proper’ material proved to be more difficult than it should have been. All that was available in Russia was black market tubing where no one really knew what exact type of material you would eventually get. Good Taiwanese frames were made out of Japanese chromoly from Tange back then, TI Reynolds in England had good chromoly as did Columbus in Italy. Chromoly was also readily available in the US so there should be a way to get some tubing, right? Thomas contacted the German steel manufacturer Mannesmann who had what he needed, but they would only sell by the kilometre - something that was way out of league for a tiny BMX company. Importing tubing was out of the question too so Wolfgang and Thomas turned to a company that specialised in roll-cages for rally cars. They could supply some of the tubing but not the very unique bike-specific sizes like the large diameter US bottom brackets for example. A warehouse full of leftover Reynolds tubing from the bankrupt French bike company Motobecane came to the rescue and so, after a few successful collaborations with the Russian company to create handlebars and seatposts, the time was right to start what has been one of Thomas’ dreams all along; the first KHE frame. In what nowadays would be the equivalent of firing up Solid Works on the computer, saw Albert, Thomas and Christian walk into a hardware store and returning with a bunch of PVC tubing, a hairdryer and a hot glue gun. In a nightly frenzy they hacksawed, bent and glued together the prototype of a BMX frame in Albert’s cellar. Taking most of its proportions from the late great Dyno Compe frame, which was sort of the gold standard of freestyle frames back then, it sported a standing platform and lowered seat stays for more clearance. This fragile plastic prototype, along with a 1:1 technical drawing, the gathered tubing and a young Albert Retey was shipped to Minsk where the first proper rideable prototype was built. After a lengthy testing phase it still took about 15 month and a few more trips to Minsk but in 1993 the first batch of 100 KHE ‘Catweazle’ frames were finally ready to be shipped to shops and customers. A big step for Wolfgang, Thomas and KHE as a company.

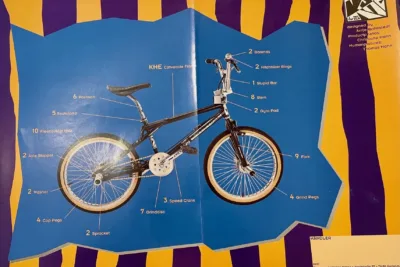

So things were looking up. Thomas and Wolfgang moved the company into its first dedicated office space. A colourful catalogue was printed showing off a complete bike built almost entirely of KHE parts. So what’s next? Well we might need another story or two for that one...

The first full catalogue (1993) featuring a stupid mugshot of Christian Wendland a some profession graphic design. Note the stem with an oversized bolt. The usual stem bolts were 10mm back then and needed to be hollow to allow cable routing. KHE introduced 14mm bolts which lasted forever.

This 1992 advert featured the first chromoly products as well as the home-sewn shinpads. Note the 'straight' and 'lowrider' stems, which were a direct reaction to the shortcomings of ACS stems.

KHE on the way to the first complete bike in 1993. The frame wasn't on sale at this point. This catalogue photo shows one of the prototypes.

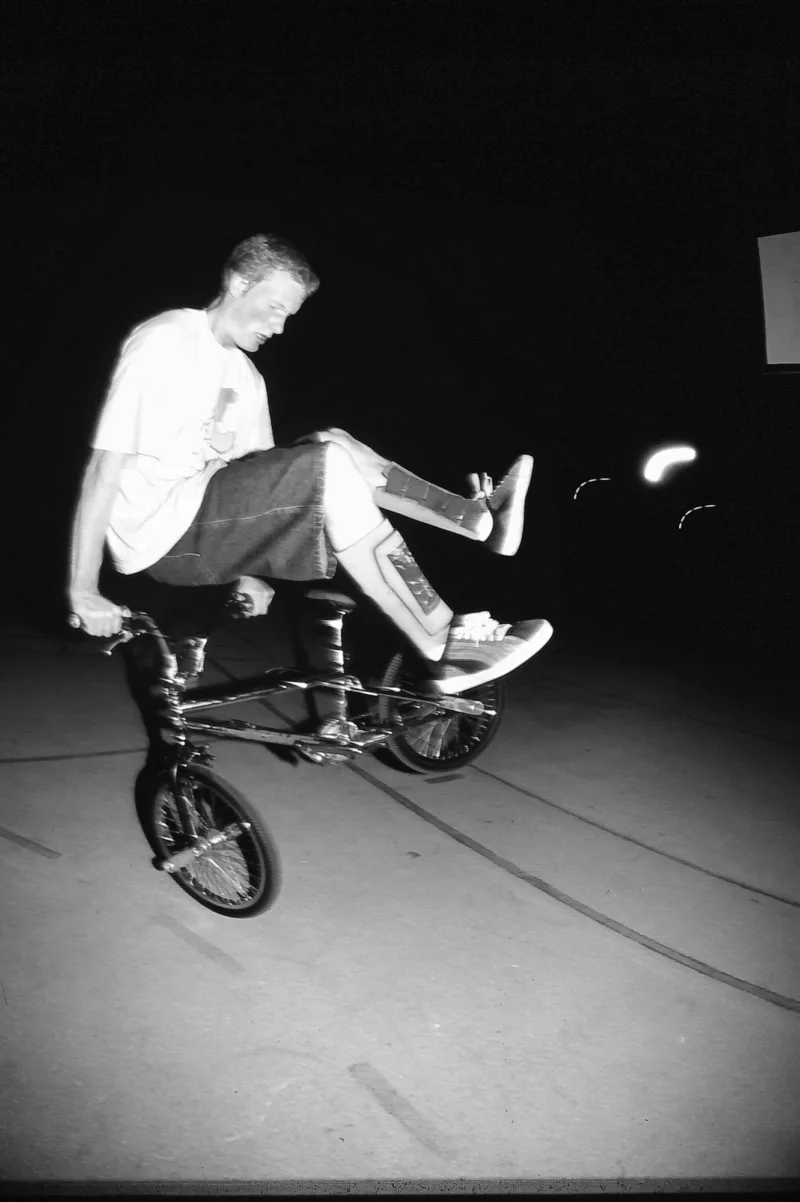

An almost complete KHE setup in action in the wild. This is Albert Retey circa 1994, mid-way though a combo he just shook out of his sleeve.

Previous

etnies 'Grounded' Memories with Joe Rich

A Video Legacy

Next

PUSHER BMX - THE 10 YEAR TRIP - IN PHOTOS

Serving the mile high city of Denver